In late 1965 a power struggle between the Indonesian army and Communist supporters of President Sukarno resulted in the killing of six generals. In reprisal, the army and its supporters carried out what might be called an anti-Communist genocide, killing hundreds of thousands of people. In some places, apparently, the purge became a porgrom against the country's Chinese minority; elsewhere it elminated anyone thought a threat to military supremacy. In many cases the killings were carried out by the premans. As the people in Joshua Oppenheimer's documentary The Act of Killing state repeatedly, the word preman derives from "free man." It dates back to Dutch rule over the archipelago, when a vrijman, initially, was a trader operating independently from the Dutch East India Company. It still carries the connotation of an independent operator, working at the edge or on the other side of the law. In modern Indonesia, the term encompasses large quasi-fascistic paramilitary organizations and petty street hustlers. Oppenheimer invariably translates preman as "gangster," but since we hear the actual word gangster used in the Bahasa language on at least one occasion we may wonder whether the director's translation is exact.

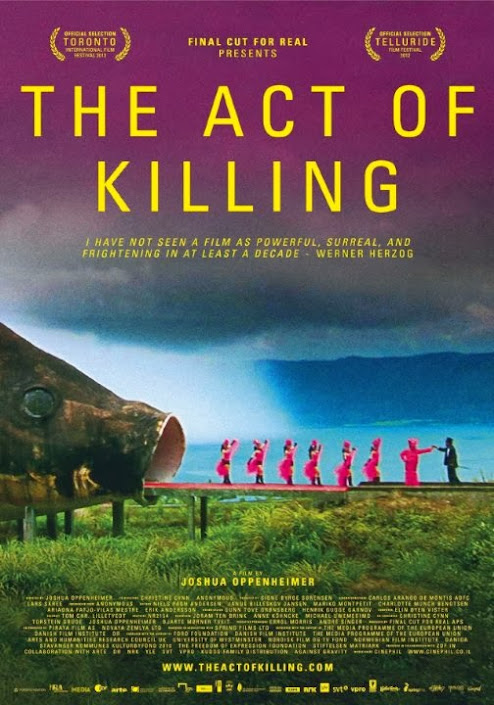

In late 1965 a power struggle between the Indonesian army and Communist supporters of President Sukarno resulted in the killing of six generals. In reprisal, the army and its supporters carried out what might be called an anti-Communist genocide, killing hundreds of thousands of people. In some places, apparently, the purge became a porgrom against the country's Chinese minority; elsewhere it elminated anyone thought a threat to military supremacy. In many cases the killings were carried out by the premans. As the people in Joshua Oppenheimer's documentary The Act of Killing state repeatedly, the word preman derives from "free man." It dates back to Dutch rule over the archipelago, when a vrijman, initially, was a trader operating independently from the Dutch East India Company. It still carries the connotation of an independent operator, working at the edge or on the other side of the law. In modern Indonesia, the term encompasses large quasi-fascistic paramilitary organizations and petty street hustlers. Oppenheimer invariably translates preman as "gangster," but since we hear the actual word gangster used in the Bahasa language on at least one occasion we may wonder whether the director's translation is exact. The premans are the subject of Oppenheimer's much-acclaimed movie, a film bearing the stamp of approval of executive producers Werner Herzog and Errol Morris, modern masters of the documentary form, and more people named "Anonymous" in the crew than you're likely ever to see in another film. Many people played a role in putting the film together, including more than can safely take credit, but inevitably we see the influence of the two celebrity auteurs, that of Morris in the frank confessions of atrocities by their perpetrators, that of Herzog in the gratuitously weird dramatizations the perpetrators are encouraged to perform. The film's peculiar conceit is that some of the surviving killers from 1965, still widely regarded as heroes in their country, were invited to reenact their deeds in the styles of their favorite movies. Deeply influenced by Hollywood cinema, they envision themselves as noirish tough guys or in kitschy musical numbers. If Herzog and Morris loom over the film as guiding spirits, Oppenheimer's finished product sometimes suggests Shoah as produced by Bialystock and Bloom.

The film's own Bialystock and Bloom, or its Franz Liebkind and Roger DeBris, are Anwar Congo, apparently one of the most famous preman killers of the era, and his protege Herman Koto. Dark-skinned and grey-haired, the grandfatherly Congo might be Nelson Mandela's evil twin; Koto is a present-day preman and the film's most ludicrous figure. The pettiest of criminals, he enjoys dressing up to the point of wearing drag in the picture's already-iconic production numbers. During the filming Koto runs for political office. While relishing the shakedown opportunities within his grasp he proves an incompetent campaigner, incapable of remembering his lines and unable to provide the presents that otherwise apathetic potential voters expect. He's more in his element in the sadistic movie-movie world Oppenheimer creates for him, while other prominent premans worry that Koto and Congo may reveal too much. They fear that too frank a portrayal of the purge will undermine their standing in history by showing that they, not the Communists, were the cruel ones.

It's a weakness of the film that it offers no context for the premans' assertion that Indonesia's Communists were cruel; there's no mention of the killing of the generals, for instance. My point isn't to justify the purge, since the crimes against actual or purported Communists far outweigh those few killings, but to note how little Oppenheimer really says about Indonesian history and how much he seems to take for granted about it. I worry that he wants us to see the premans as equivalent to American right-wingers, given their anti-Communism and their proud "free men" identity, though they give little evidence of ideological motivation. The biggest gripe against Communists expressed in the picture is that local governments taken over by the PKI reduced the number of Hollywood movies that could be shown in theaters, thus reducing the take for preman ticket scalpers. The perception that the premans aren't motivated by ideological fanaticism probably explains why The Act of Killing has been described as an illustration of the "banality of evil." But Anwar Congo is no Adolf Eichmann. He readily takes responsibility, if not credit, for mass murder. He says "we had to do it" at one point, but I don't think he means that he was just obeying orders. For Hannah Arendt, the banality of evil was rooted in oppressive institutions' empowerment of mediocrities like Eichmann who remained little more than instruments of an institutional murderous impulse. The premans have more agency than Arendt seemed to grant to Eichmann, while Oppenheimer seems more concerned with their banality as personalities than with the banality of institutionalized evil. At its worst, The Act of Killing seems to be about the kitsch or camp of evil, Herzog-style, and it's hard to tell whether the director wants us to be horrified more by Congo's crimes or by his apparent bad taste -- whether he means viewers to judge Congo by their horror or their laughter.

Until the final reel I was ready to dismiss The Act of Killing as a profoundly overrated piece of condescending, vaguely racist camp from a Herzog-wannabe. Its message seemed to be, "What benighted savages these Hollywood (or Bollywood?)-addled Indonesians are, playing soldier and gangster after killing multitudes." Then something remarkable happened. For Oppenheimer, the problem of evil in Indonesia had been that no one, or nearly no one, acknowledged that what had happened was evil. The kitschy reenactments seemed to illustrate the perpetrators' unrepentant attitude toward their deeds. But in the course of the playacting Anwar Congo takes on the role of a victim of the crimes he actually committed. Early, we'd seen him demonstrate the neat way to kill a man by strangling him with a wire. Later, he submits to the same treatment. It's only a movie -- in fact, it's only a movie within a movie -- but imagining himself on the receiving end he has a sort of epiphany of empathy, if your definition of epiphany includes a loud bout of the dry heaves. Congo had already imagined himself haunted by nightmare demons, but also as receiving absolution from the ghosts of his victims, one of whom is shown in a production number thanking Congo for saving his soul by killing him. Congo wants the film to vindicate him, but for one moment, at least, it breaks him. Against the odds, Oppenheimer's strategy worked -- if it had been his strategy, after all, to force a moral awakening on his subjects. The play was the thing to catch the conscience, if not of the king, then of his knight. No real or lasting repentance resulted, I suspect, but Congo's moment of remorse and revulsion will live as long as the footage does, and it's what the world outside Indonesia will remember him for. Small solace for his victims and their survivors, certainly, but at least it suggests that history will take their side.

1 comment:

You do make an excellent point there about the whole matter of the communists never being properly framed as evil and worthy of obliteration. The satire in this film lacerating. Agreed the last "reel" is best, but the film works throughout via the shock quotient. Terrific review!

Post a Comment