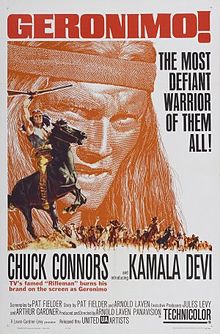

Arnold Laven's widescreen western isn't Hollywood's most convincing portrayal of Native Americans,but its heart seems to be in the right place. Working with his Rifleman producers between seasons and co-starring with future wife Kamala Devi on the rebound from a divorce earlier in the year, Chuck Connors is too young and probably too big to match the historic image of the Apache chief. As his buddy Mangas -- probably an allusion to Mangas Coloradas, Ross Martin makes Connors look like Wes Studi. I understand that in Laven and Pat Fielder's screenplay Mangas represents an over-domesticated Apache, but Martin works the theme too hard, coming across more like Geronimo's slightly effete suburban neighbor than his fellow warrior. Whatever Connors lacks in authenticity, however, he compensates for with heroic authority, and that's probably the best to be expected from Laven's earnest attempt to identify Geronimo as an American hero. This film probably does more toward that end, in the sense of turning the Apache into a kind of storybook hero, than the John Milius-Walter Hill version with Studi in the title role from 1993. The Laven film also focused my thoughts on a subject that had been rattling around in my mind for a while. It occurred to me that Laven and Connors's Geronimo could be seen as a hero just as easily by right-wingers as by left-wingers, and that in general, since the advent of the sympathetic Indian motif around 1950, the Indian defender of his land, people and way of life has been one of the few heroic symbols that right and left can agree on, even though each side arguably admires them for different reasons.

Arnold Laven's widescreen western isn't Hollywood's most convincing portrayal of Native Americans,but its heart seems to be in the right place. Working with his Rifleman producers between seasons and co-starring with future wife Kamala Devi on the rebound from a divorce earlier in the year, Chuck Connors is too young and probably too big to match the historic image of the Apache chief. As his buddy Mangas -- probably an allusion to Mangas Coloradas, Ross Martin makes Connors look like Wes Studi. I understand that in Laven and Pat Fielder's screenplay Mangas represents an over-domesticated Apache, but Martin works the theme too hard, coming across more like Geronimo's slightly effete suburban neighbor than his fellow warrior. Whatever Connors lacks in authenticity, however, he compensates for with heroic authority, and that's probably the best to be expected from Laven's earnest attempt to identify Geronimo as an American hero. This film probably does more toward that end, in the sense of turning the Apache into a kind of storybook hero, than the John Milius-Walter Hill version with Studi in the title role from 1993. The Laven film also focused my thoughts on a subject that had been rattling around in my mind for a while. It occurred to me that Laven and Connors's Geronimo could be seen as a hero just as easily by right-wingers as by left-wingers, and that in general, since the advent of the sympathetic Indian motif around 1950, the Indian defender of his land, people and way of life has been one of the few heroic symbols that right and left can agree on, even though each side arguably admires them for different reasons.Right-wing historians may remain apologists for American westward expansion, but you don't really see their case represented on film in modern times. That may not surprise some observers given presumptions about the biases of moviemakers, but the more interesting omission to me is the lack of complaint against films portraying Native Americans as heroes in struggle against the United States. You don't hear the usual suspects accusing Hollywood people of being "Indian lovers" or demanding that the "truth" be told about the First Nations. It's not as if this topic hasn't had time to simmer. The advent of the sympathetic or heroic Indian happens around the same time as the rise of the modern American right. Delmer Daves's Broken Arrow appeared in 1950, the same year that Joe McCarthy made his first high-profile denunciations of Communist subversion. Laven's Geronimo came out as Barry Goldwater's supporters were building the movement that would win him the 1964 Republican presidential nomination and change the course of political history. My argument is that those Goldwater people were less likely to find Geronimo's narrative of wicked, greedy white men (Adam West is an ineffectual exception) insultingly anti-American than they were to accept Laven's premise of the Apache as a heroic representation of a certain type of American. The key to the argument is an assumption that when the left idolizes or idealizes Indians, they always see Indians as the oppressed Other, a reminder of their perpetual guilt, while when the right idealizes Indians, they see in Indian heroes reflections of themselves.

Laven sometimes bends over backwards to make sure Geronimo remains purely heroic. The film's most implausible scene has some of Geronimo's starving warriors breaking into a farm storehouse to steal oats. The farm woman catches them shoveling oats into their mouths and has the drop on them before Geronimo appears behind her. When he explains how hungry his men are, the woman nervously invites them to her dinner table and fixes them some fried chicken. She strives to impose discipline, ordering them not to dig in until she says Grace and then rebuking one warrior who tosses a leg bone onto the floor. He doesn't take that well, but Geronimo defuses the situation by ordering the other men out of the house. He then pointedly tosses a bone on the floor himself, which the woman takes as a prelude to rape. She warns him that her husband, a trapper, could be back at any moment, but he's deduced that she's a widow. He comments that her husband survives in their son, who has fearlessly watched the whole spectacle, and goes on his way more determined to have a son of his own by Teela (Devi) the educated reservation Apache he has claimed as his wife. Maybe I'm prejudiced, but given the desperate circumstances it seems unlikely that this scene could have played out without any violence. But the sympathetic Indian is often portrayed as living by higher ideals, whether they be left-friendly notions of harmony with nature or a code of honor (or even chivalry) rightists might identify with their own values.

My point isn't that Geronimo is a right-wing movie, but that despite pro-Indian films like this one there seems little felt need for a "right-wing" movie about Indians, if you presume for the sake of argument that a right-wing western would adopt the older viewpoint (which really wasn't as universal pre-1950 as film historians sometimes suggest) that Indians were mere savages who had to be subdued for civilization's sake. While we take for granted that sympathy for Native Americans is a "left wing" stance -- it wasn't necessarily so for much of our history -- that doesn't oblige right-wingers to disparage Indians just to be contrary. There's no automatic inconsistency in someone like the old western TV star Clint Walker, for instance, championing Indian causes -- he's one-quarter Cherokee -- while being such a rabid right-winger that he needs to rant on the radio sometimes. My own father was proud of his Native blood while professing Republican views, though they were probably more mild than Walker's. It was probably inevitable as the frontier closed and Indians ceased to be a clear or present danger to settlers that mainstream American culture would look more favorably upon them, though it did take a while for the balance to shift significantly in Indians' favor. That shift has not been challenged by the American right, but has been, to all appearances, endorsed by them. Native Americans may not have the same symbolic flexibility for non-Americans; it would explain why Indians figure so rarely in spaghetti westerns compared to Mexicans, the different emphasis perhaps reflecting Italians' greater concern with class conflict (which can be played out more starkly in a Mexican context) or imperialism. On the other hand, Indians loom large in German westerns thanks to the enduring popularity of Karl May, whose tales of heroic Indians were boyhood favorites of Adolf Hitler -- which I guess only proves again the potency of the Native American as a symbol that transcends typical thinking about race as well as ideology. How you feel about Indians and the Indian wars may not predict your political beliefs -- but it may make them more complex than people assume. Knowing that makes watching Indian movies, even middling entertainments like Laven's likably energetic effort, a more thought-provoking experience.

1 comment:

You can also say that for the right they can relate the struggles of Native Americans to their struggles against the federal government "meddling" with the states i.e. the civil rights struggle

Post a Comment