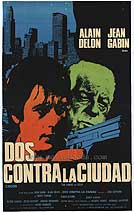

Jose Giovanni was a major figure in French crime literature and crime movies. A former death-row inmate, he became a writer whose novels inspired such classics as Claude Sautet's Classe Tous Risques and Jean-Pierre Melville's Le Deuxieme Souffle. Eventually Giovanni wrote and directed his own movies; I reviewed one of them, Le Gitan, earlier this year. Like that one, Deux Hommes Dans la Ville features Alain Delon, who produced the film. Unlike Le Gitan, Two Men In Town (known in England as Two Against the Law and in one Spanish speaking country as Two Against the City) is an impassioned act of rebellion against the crime genre if not against the entire concept of the "criminal" as a personality type.

Jose Giovanni was a major figure in French crime literature and crime movies. A former death-row inmate, he became a writer whose novels inspired such classics as Claude Sautet's Classe Tous Risques and Jean-Pierre Melville's Le Deuxieme Souffle. Eventually Giovanni wrote and directed his own movies; I reviewed one of them, Le Gitan, earlier this year. Like that one, Deux Hommes Dans la Ville features Alain Delon, who produced the film. Unlike Le Gitan, Two Men In Town (known in England as Two Against the Law and in one Spanish speaking country as Two Against the City) is an impassioned act of rebellion against the crime genre if not against the entire concept of the "criminal" as a personality type.Producer Delon plays the main character but generously cedes top billing to then-living legend Jean Gabin. At age 69, Gabin was near the end of his run, and his elderly, authoritative presence is equivalent to Jimmy Stewart, say, playing a similar role in an American film of the period. Often a tough guy in his own vehicles (I've seen too few of them), Gabin this time out is Gervaise Cazeneuve, a kind of guidance counselor to prisoners awaiting parole, and a mentor in particular to Gino Strabliggi (Delon), who's served ten years for robbery as the picture opens. Gervaise pleads hard for Gino's release against skeptical authorities who see him as nothing but a career criminal. From the first, viewers familiar with crime movies will anticipate where the story goes.

As a parolee, Gino is barred by French law from living in major cities or port towns. Gervaise looks on happily as Gino is reunited with his faithful wife, a florist, and helps his charge find work as a printer. A nearly-familial bond develops between Gino and the entire Cazeneuve brood, including a daughter who has an obvious crush on him. He has the fortitude to resist temptation when some old criminal cronies try to lure him back to the life, and he's serenely unimpressed by the insults hurled by a young punk played by up-and-coming Gerard Depardieu. When the punk sneers that Gino has grown soft, Gino simply says it must be so.

Gerard Depardieu has only one scene with Alain Delon in Two Men in Town, and director Jose Giovanni missed the opportunity to unite three generations of French superstars by having Jean Gabin in the shot.

Both criminals and cops assume that it's only a matter of time before Gino goes bad again, and for a while after his wife dies in a car wreck and he sinks into an antisocial funk it looks like he might out of sheer boredom or despair, but his bond with the Cazeneuves keeps him straight until he lands a job in another town and falls in love with Lucie, a half-English bank employee (Mimsy Farmer). He's a good worker whom his boss hopes to make his partner, and this support gives him the confidence to rebuff the crooks yet again when they jump to the conclusion that he's hooked up with Lucie just to get an inside angle on the bank. Sharing their suspicions is Inspector Goitreau (Michel Bouquet), the flic who busted Gino years ago and refuses to believe in his reform. He shadows Gino with increasing determination and tries to undermine the confidence his boss and girlfriend have in him. Finally, when the gang robs the bank themselves, Goitreau is desperate to link Gino to the crime, increasing the pressure on Lucie until Gino snaps at last and beats the flic to death.

Michel Bouquet (top) makes things increasingly difficult for Delon and Mimsy Farmer (below)

That was no spoiler because the ultimate drama of Deux Hommes is whether Gino, who has clearly done wrong but was clearly provoked beyond reason by a mean-spirited cop, will get the death penalty. This is an issue of obvious interest to a writer who did time on death row himself, and the whole film is an indictment of the French criminal-justice system. In his view, the fact that France still used the guillotine in the 1970s betrayed the nation's claim to be a world cultural leader. As Gabin says at the end of the film, the entire system is a killing machine, and a big part of that fatal system is the merciless categorization of people who had bad breaks and made mistakes as "criminals" who are exiled from much of life and condemned to perpetual suspicion as if they're all vicious by nature. I wonder whether Deux Hommes was in some way a mea culpa for Giovanni, who might have felt that his own earlier writings and the films made from them contributed to the idea of a criminal archetype that obscured the humanity of real people who happened to commit crimes. The film makes an interesting counterpoint to Straight Time, a film made from a novel by an American ex-con who seems to embrace the idea of a criminal as a certain character type with a particular moral code and lifestyle. You might ask whether the main character in each film is meant to be exceptional or typical, and it might be a weakness of Giovanni's film that you're not sure of the answer as far as Gino's concerned. He seems almost too good to be true until the cop wrecks his life (and the flic himself isn't much more than a caricature), but Giovanni may have thought that in this case the exception disproved the criminal stereotype that he opposed.

Two Men in Town may be a critique of Giovanni's own work, but it also seems at times like a riff on some themes in American crime films of the 1930s. The idea that society, if it didn't make Gino a criminal in the first place, remade him as a criminal through a self-fulfilling prophecy, has a familiar ring to an American ear. The final scene reminded me of the death-house climax of Angels With Dirty Faces. In that film, the lingering question is whether Cagney feigned fear to give the Dead End Kids an anti-role model of criminal cowardice, or whether his fear was unfeigned because he really was a cowardly criminal. Giovanni and Delon predictably dispense with the Hollywood histrionics, but the writer-director makes a point of having Delon state simply to Gabin, "I'm scared." The point isn't to prove something about the criminal mind, but to remind us one more time that Gino Strabliggi is a human being. It's a tribute to Delon's commitment to the project that he sells the fear and vulnerability with understatement. As an actor, he's contributed to the criminal archetype with numerous too-cool badass performances, and he'd give another for Giovanni in Le Gitan, but here he has to transcend the archetype, and he does. As for Gabin, his job is to narrate, act as a surrogate father-figure for Delon, and express the auteur's bruised, despairing idealism. It must have been something for French audiences to see him do it, but others probably need a crash course in Jean Gabin to get it.

Deux Hommes is a genre-defying film. People who watch it expecting something like a Melville film could easily be disappointed, but the director and the cast should make it an item of automatic interest for French crime fans, who'll at least go away with food for thought.

Here's the French trailer, uploaded by Annie7676. There's no English translation, and there wasn't any on the Kino DVD either. You do get a chance to hear some of the great, mournful score by Philippe Sarde.

No comments:

Post a Comment